Over the past couple of months, I’ve been diving into rabbit holes, consuming lots of content from Miles Grimshaw on the podcast Invest Like the Best to Ray Dalio’s Principles to Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist which I read because of a Bill Gurley podcast with Tim Ferriss. The problem is that I have already forgotten a lot of the learnings. Fun fact: humans forget about 80% of everything we see on a daily basis.

“Your mind is for having ideas, not holding them” - David Allen

A simple idea that has already revolutionized the way I learn: I started to write down what I consumed. The reasons why all mimic my “On Writing” post, except I originally thought my “On Writing” post only applied to longer form writing; I hadn’t realized how much writing fragmented sentences or short paragraphs could help me in understanding what I was consuming. However, although I was able to retain and understand better when I wrote bits of information down, I couldn’t connect these ideas across the various blogs, podcasts, books, newsletters, and tweets I was consuming. This led me to the question:

Is there a way to digitally capture content in a way that helps foster linkages between the content so that I am better able to find connections that lead to more creative thinking and innovations?

As a personal experiment, I have tried to foster these linkages in my own “digital garden”. One thing that struck me was the inefficiency and ineffectiveness of the current processes for knowledge creation and insight formation. Current structures and formats limit one’s ability to think more creatively and come up with innovative ideas.

I have begun to form the hypothesis that better “Tools for the Mind” could unlock a ton more potential for innovation. And Innovation is the key or linchpin for personal, societal, and economic growth and progress. The engine to propel humanity.

I hope to convince you by the end of this article that there is a way to foster innovation and tools can be built to unlock this economic growth and progress.

To briefly walk through this article so you can keep track, I argue:

Innovation is important

Innovation isn’t random but systematized

The current way we create work has a lot of structure. That structure is bad

The best way to create is a node network

Then I ask: could we power a node network with AI to interact, learn, and build off its pre-existing nodes?

Businesses are always looking to grow, expanding their market to try to capture as much value as possible whether by increasing the revenues from their current customers or acquiring new customers. Investors use proxy metrics to judge this progress meticulously. For software companies, investors look at YoY annual recurring revenue to judge customer demand and product top-line growth. They look at net-dollar retention to judge the a company’s ability to retain and secure more revenue from these existing customers. Intuitively, this makes sense. Without growth, it is only a matter of time before a company dies. Although it is not the only one, the main driver behind company growth is innovation.

To me, innovation is like a frontier, where the leading edge of progress in a given industry or field is embodied in different products or services offered to customers. The innovation that is embodied can be anything novel and useful whether that be a new process, strategy, composition of matter, product, service, or business model. Always ahead of the “innovation frontier” is the “knowledge frontier”, where the leading edge of what Paul Graham likes to call “crazy new ideas” are emerging. The region in-between these two frontiers is where innovation occurs. This region is where all opportunity lies. Businesses compete to find the next pocket of opportunity in order to capture the value that accrues. Capturing that value pushes out the “innovation frontier” stealing market share from businesses not on the frontier. The pockets of opportunity available between the innovation and knowledge frontier are called the adjacent possible coined by Stuart Kauffman and further theorized by Steven Johnson. Johnson uses this metaphor to describe how the adjacent possible works:

“Think of it as a house that magically expands with each door you open. You begin in a room with four doors, each leading to a new room that you haven’t visited yet. Those four rooms are the adjacent possible.”

Pretend you are in that house standing in the room with four doors. Here, you are currently on the “innovation frontier.” The rooms behind these four doors represent the “knowledge frontier.” When you step through one door into a new room, you have just innovated, expanding the “innovation frontier” outward by going through the adjacent possible. The new room is now along the “innovation frontier”, the new doors in that new room is the adjacent possible, and the rooms behind those new doors is the “knowledge frontier.” All growth and progress repeats this process in an infinite loop, ever expanding Johnson’s metaphorical house. Scoping this out to a 30,000ft view, here is how all these parts look visually on an efficient frontier graph:

(Digram 1 - source: https://evolutionarytree.com/content/insights-innovation-frontier)

Unlike how it is portrayed in movies, innovation does not appear out of thin air. Innovation is a systematic creation from the collection of what is already known to create something new. Innovation occurs as a first-order derivative of what is sitting on the “innovation frontier”. Therefore, part of innovation is figuring out what currently sits on the “innovation frontier”. There has to be a way to harness tools to systematically find what sits on the “innovation frontier” and identify the doors to walk through in order to innovate.

Today, not only does no tool exist for businesses but the tools used to create are rigidly structured, creating barriers which hinder these businesses from exploring opportunity. I realize I have to back that assertion up.

The three mediums of creation that all knowledge workers currently use to create new work are the document editor, the spreadsheet, and the presentation maker. The two main players that provide these mediums of work for companies to use is Microsoft 365 (345M paid users) and the G-suite (3B users). Let’s walk through an example process of creation.

Scenario A - Student at University of Michigan:

Arrive and sit down in business economics class. Click onto google drive, navigate to “junior year” folder —> “business economics” folder—> “unit 3” folder —> and click to open “business economics lecture 15”. In class, learn a new nugget of knowledge, and write it down in the document.

Scenario B - Head of strategy at Palantir :

Enter a meeting with team to brainstorm a new market opportunity. Navigate to “strategy” folder —> “2023” folder —> “blue ocean” folder —> “market X brainstorm” document. Hold great brainstorming session and come up with a couple nuggets of information to write down in a document.

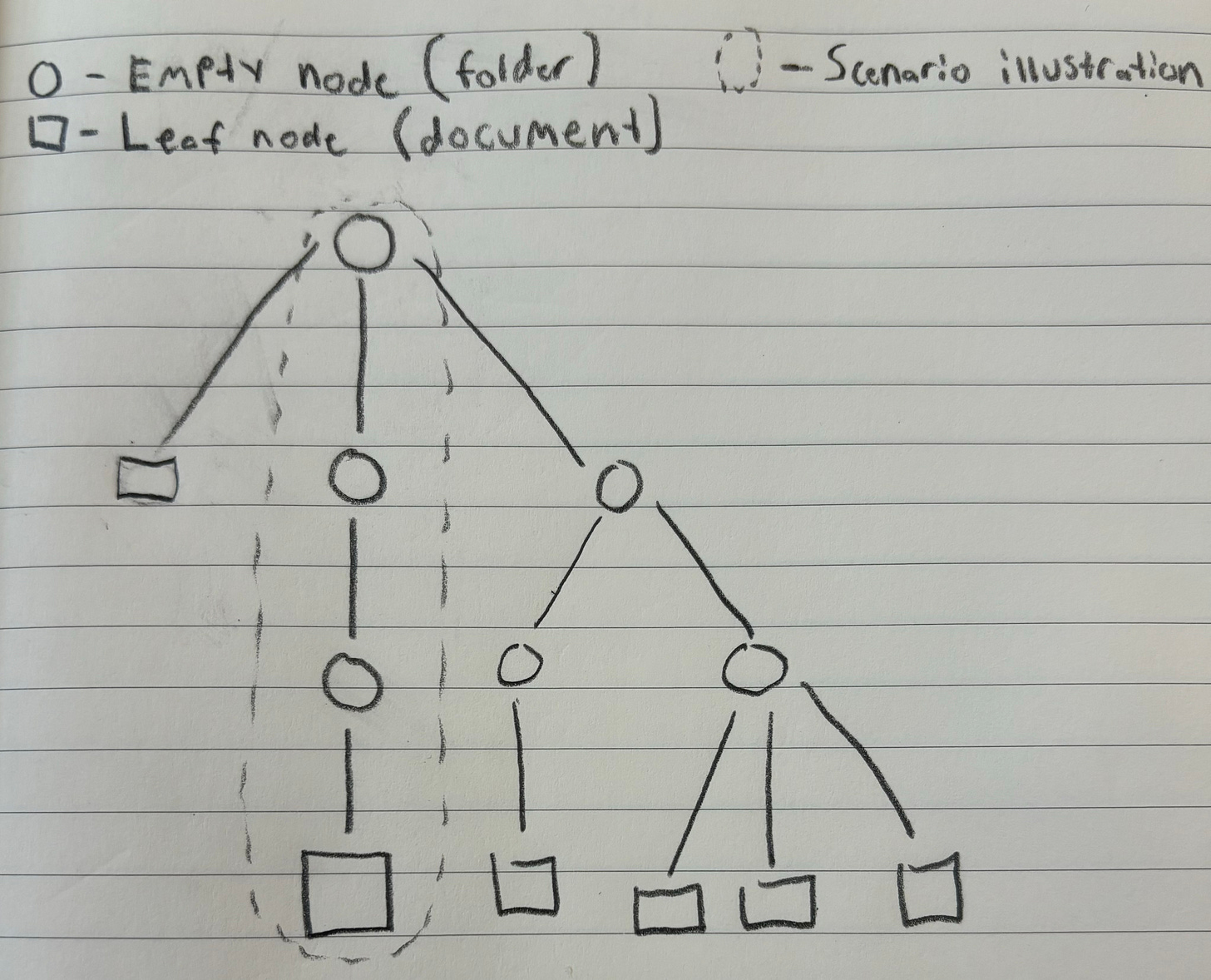

Both of these scenarios describe how we create, store, and retrieve information. When you create one of these three different mediums, you have just created a leaf node in the universe. Within this leaf node information is stored. If you store the document within a folder, you have created a link between the new leaf node and the folder (an empty node). That empty node might link to higher empty nodes. Visually both of the scenario’s node networks look like this:

(Diagram 2 - source: self-sketch)

I don’t think I would be overreaching to say this is how almost all information is created, stored, and retrieved.

When you create a document, you are inherently creating structure. The benefit of structure is that it allows you to retrieve that information later. Today, most businesses and people prioritize rigid structure to optimize retrievability. But structure restricts innovation. Because good ideas are building blocks that lead to new good ideas, we need to find the current building blocks sitting on the “innovation frontier” to innovate. But these good ideas come from all over; they are not restricted to the specific niche you are writing down in your “business economics lecture 15” or “market X brainstorm” document. Rather these epiphanies happen connecting ideas across various seemingly unrelated areas. Therefore, these building blocks should not be sitting in isolation siloed by structure of the rigid hierarchy in which it is stored. These building blocks need to interact with other building blocks on the “innovation frontier” to find those adjacent possible opportunities.

It is not a novel concept that structure breeds limitation. In fact, it has been studied widely from the lens of how computers create, store, and retrieve information: Data Warehouses versus Data Lakes. A Data Warehouse stores data in a structured format with a central repository of preprocessed data for analytics. Data Warehouses operate in a very similar way to Scenario A and Scenario B described above: data stored within a rigid hierarchical structure. However, as the sheer volume of data exponentially increases, it becomes increasingly important to transition from the hierarchical structure (Data Warehouses) to flat structures (Data Lakes) where companies dump their unstructured, semi structured, and structured data into a centralized flat repository. Why? It removes data silos which allows companies to efficiently pull data across multiple different fields for better insights. For example, let’s say a company has a vast amount of marketing data from social media comments, ad engagement metrics, and media data files. With a flat structure, the company can pull data from each of these sources to get a more nuanced analysis of marketing trends than if the company could only perform an individual analysis of the siloed data. Databricks has built a $43B company based off this Data Lake idea.

Although there are fundamental differences between the information computers and humans create, there are also similarities. For instance, the sheer volume of information humans now take in on a daily basis has exponentially increased as well.

(Diagram 3 - source: https://www.valamis.com/blog/why-do-we-spend-all-that-time-searching-for-information-at-work)

This jump in volume increasingly makes it harder for us to know what information is on the “innovation frontier” and harder to connect those ideas due to the rigid hierarchical structure we use today to create, store, and retrieve information.

Therefore, the best way for people and businesses to create, store, and retrieve information is a flat data lake structure. Rather than a leaf node connected to empty nodes up a single branch as shown in Diagram 2, pockets of information should be connected across each other in a flat node network:

(Diagram 4 - source: https://www.data-to-viz.com/graph/network.html)

This flat structure removes the barriers and information silos, helping to systematically connect ideas, insights, and inspirations. If this is hard to conceptually grasp, try playing around with my “digital garden” I briefly mentioned in the introduction. It uses the idea of this flat structure to link ideas, insights, and inspirations together in order to help me think more creatively and come up with innovate ideas. Any time I find a useful piece of information, I write it down in my “random thoughts” page. This page is what I consider to be my “information lake” where all structured, semi structured, and unstructured information arrives (these are all the nodes pictured in Diagram 4). If I think that random thought relates to another node, I create a link the two nodes (these are all the lines that connect the nodes to each other pictured in Diagram 4). Over time, dense clusters of nodes start to form around specific areas and I group them together into a higher level topic or category to see where my learning is developing and where to research more. This is my personal “knowledge frontier”; I am continually grouping, adding, and weeding to push my “knowledge frontier” outward. My personal knowledge frontier is far behind the “innovation frontier” of any particular industry or sector. But when I get to the point where I am finding and understanding “crazy new ideas” sitting on the knowledge frontier of some specific industry, I will start to have the ability to find the adjacent possible and create economic growth and progress by expanding the “innovation frontier” outward. Here is a portion of my digital garden’s flat node network:

(Diagram 5 - source: my digital garden)

Although this not the primary use-case for notion, they offer the ability to create this flat hierarchical structure through their by-directional linking. There are also note-taking tools that have built their software solely off this idea, notably Roam Research currently worth 200m according to Pitchbook. It has captured this value because it increases the productivity of their consumers by a substantial margins, some claiming a near 3x increase. Anecdotally, I might argue my “digital garden” increases my productivity by more than that.

However, I don’t think the opportunity stops at a tool like Roam Research. No, not at all. What if when you attach a link it not only connects but could harness the information from the other nodes to power this new node you are creating? What if the node you are creating automatically knew which other links to attach to? I want to make this network start to think for itself and these mediums of creation start to do the work for you. The document editor has been about formatting words, not creating them. Konstantine Buhler, partner at Sequoia, writes “the big emerging opportunities for doc editors in the age of generative text is to innovate on the writing experience itself.” The new experience would be to harness and find connections of other mediums that you or your organization has previously created. Why keep a node network to just one person when the whole organization could create and benefit from each others work? Other than privacy, which could be accounted for, I don’t see a reason.

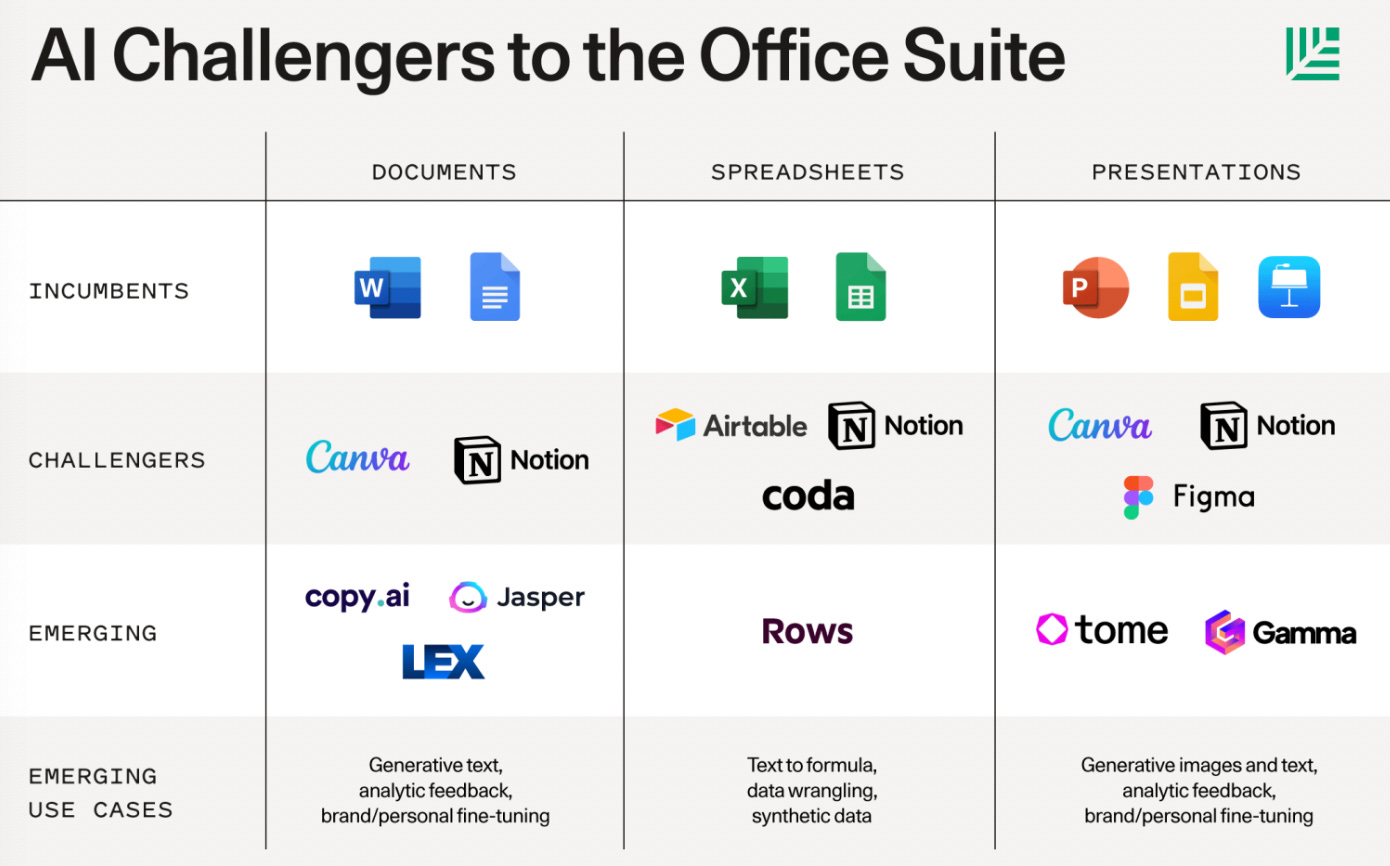

The embodiment of this idea into a product would be a new way to create documents, spreadsheets, and presentations. Buhler believes that there will be disruption in this space, creating this graph to showcase opportunity:

(Diagram 6 - source: https://www.sequoiacap.com/article/ai-for-work-perspective/)

Buhler is thinking about it wrong though. He is creating structure by bucketing each of these types of mediums into distinct categories when they should really just be one: the medium of creation. These mediums of creation will work off each other to help the knowledge worker create more. Sure, I think this will help with repeatable work knowledge workers forgot about or don’t want to do. But I think the real opportunity is helping find the “innovation frontier” and adjacent possible opportunities through this systematic approach.

The rise of generative artificial intelligence has unlocked the possibility for this opportunity. Specifically, I am thinking about the ecosystem of tools that can be used to create this software application. Pinecone is one that creates vector embeddings to create search results based on similarity; Superlinked is another that can take the mediums of creation and turn them into vector embeddings.

I envision a new way to create for knowledge workers. When you open a document editor, spreadsheet, or presentation, it knows the previous insights you or your company has and surfaces the relevant ones so you can instantly find the “innovation frontier” and work on finding those adjacent possible opportunities.